Tech Lessons Learned through COVID-19

Tech Lessons Learned through COVID-19

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, most, if not all of us, turned to technology as the primary avenue to prepare our teachers. We used Google folders and documents and lots of Zoom and TEAMs. At Florida International University (FIU), it heightened our awareness that well-prepared beginning teachers of mathematics should be ”proficient with tools and technology designed to support mathematical reasoning and sense making, both in doing mathematics themselves and in supporting student learning of mathematics” (AMTE, 2017, p. 11). Based on our experiences, we felt that our preservice teachers (PSTs), even though considered ‘digital natives’ or the ‘Net generation’, had much technology knowledge and skills to learn to use online technologies for themselves as well as for teaching students. The existing research supports our observations (e.g., Dincer, 2018; Etmer, 2005). Thus, in 2020, we decided to investigate our PSTs’ development of self-efficacy for teaching mathematics with online technologies within our methods of teaching courses. At the AMTE 2021 Conference, we shared our work (See our AMTE 2021 Presentation Handout) and were invited to Blog about it here.

Revisions to Our Methods

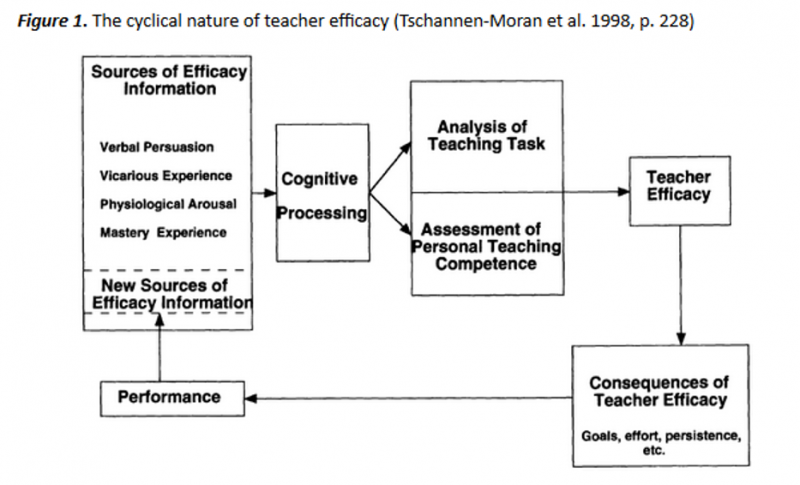

To promote PSTs’ development of self-efficacy for teaching with online technologies within our two methods courses (one elementary and one secondary), we drew on the work of Tschannen-Moran et al. (1998) (see Figure 1). Since mastery experiences are the most powerful source of efficacy information, we developed activities for each course that provided such experiences for our PSTs including peer microteaching involving the use of online technologies, virtual manipulatives, and simulations. We also developed experiences that encouraged community building involving the online technologies to promote physiological arousal through positive emotions. Additionally, we provided vicarious experiences involving the online technologies such as instructor modeling of online synchronous teaching, as well as peer modeling during peer teaching experiences. Finally, verbal persuasion was supported through interactions with the instructors, and also their peers during whole-class and small-group activities.

Our Findings

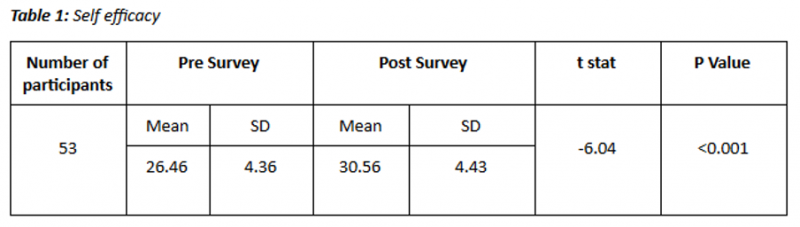

We gave a pre- and post-survey to 53 mathematics education PSTs in our elementary and secondary methods courses during summer and fall in 2020. The survey included questions about their familiarity with online teaching tools, as well as a self-efficacy for teaching online using a 9-point Likert scale adapted from the MNESEOT Survey Instrument (Robinia, 2008; Robinia & Anderson, 2010) with reliability of 0.91 and based on the work of Tschannen-Moran et al. (1998). Our PSTs’ scores on their self-efficacy in teaching with technology in an online synchronous setting improved significantly from pre to post (see Table 1).

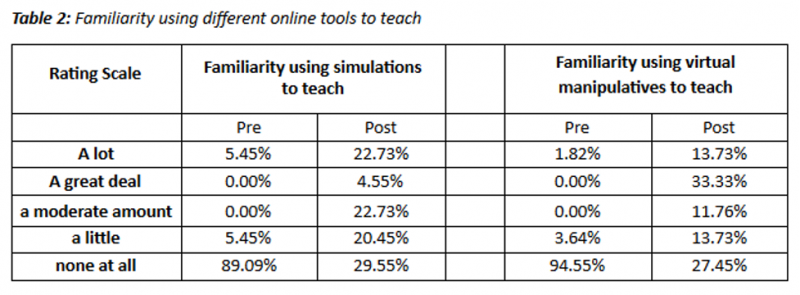

Additionally, the PSTs reported developing their knowledge, skills, and familiarity in using online technologies for teaching mathematics. See Table 2 for examples of their growth. Our PSTs chose tools (simulations or virtual manipulatives) that were most appropriate for their lesson/ topic to teach their peers which affected their growth in familiarity for teaching with each. Their responses to familiarity with these tools as students showed even greater growth.

Overall, 84% of the PSTs indicated they would likely incorporate simulations or virtual manipulatives to teach lessons in the future.

Lessons We Learned

Given the extent of our PSTs’ growth in using online technologies for teaching during just one methods course and the importance of these tools now and in the future, we are rethinking how much and in what ways to better incorporate these technologies in our courses. Here we share some lessons we learned that apply to teaching face-to-face, along with other settings. For more details, links to tools, and information see our 2021 AMTE Presentation Handout.

- Require the use of Virtual Manipulatives/Simulations as part of lessons and activities PSTs use to teach either peers (or in field placements) to develop their self-efficacy in using them; otherwise, they may not use them in their lessons - we experienced this in an initial assignment.

- Discuss and model the use of online tools for different purposes such as tools specific to mathematics, tools for collaborating, and tools for assessment to help PSTs gain familiarity.

- Establish a baseline for tools being used extensively - be mindful that some students may not have access to resources like printers or printer paper.

- Do not assume PSTs know how to use the features of general technology tools, even if they have been using online tools for prior classes (e.g., Google Drive folder settings, Snipping/Grab for screenshots).

- Create a Google Drive “Class Folder” at the beginning of the term with correct editing permissions, as appropriate, and add daily class session folders with individual or group documents that PSTs can share and collaborate on for the given class session.

- Use consistent group names across Google Docs and Breakout rooms to easily monitor progress in collaborative activities.

- Label the group documents with short names (e.g., GRP1, etc.) so the course instructor can easily check on any group’s progress through the Google Doc Tab across the browser window.

References

Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators. (2017). Standards for Preparing Teachers of Mathematics. Available online at www.amte.net/standards .

Dincer, S. (2018) Are preservice teachers really literate enough to integrate technology in their classroom practice? Determining the technology literacy level of preservice teachers. Education and Information Technologies. 23,2699–2718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-018-9737-z

Ertmer, P. (2005). Teacher pedagogical beliefs: The final frontier for technology integration? Educational Technology Research and Development, 53(4), 25-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02504683

Fernandez, M. L., Fatima, S., Forde, E., & Park, J. (2021). PSTs’ Self-Efficacy for, Knowledge of, and Skills in Teaching with Technology for Remote Learning (Handout). 2021 Annual Conference of the Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators (Virtual), February 11-13, 2021.

Robinia, K. A. (2008). Online teaching self-efficacy of nurse faculty teaching in public, accredited nursing programs in the state of Michigan.

Robinia, K. A., & Anderson, M. L. (2010). Online teaching efficacy of nurse faculty. Journal of Professional Nursing, 26, 168–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2010.02.006

Tschannen-Moran, M., Woolfolk-Hoy, A. W., & Hoy R. (1998). Teacher efficacy: Its meaning and measure. Review of Educational Research, 68(2), 202-248. https://doi.org/10.2307/117075